Mitsuro Yoshida, director of both Super Dodge Ball and River City Ransom, has died. He was 61.

Yoshida’s full career may seem inscrutable to Americans, where, from our perspective, he directed two hits more than 30 years ago for a company, Technos Japan, that declared bankruptcy in 1996. Yoshida worked for the company during the heydey of the side-scrolling arcade beat-em-up, a blockbuster trend that ruled arcades between 1987-1990 (between the release of Double Dragon and before the arrival of Street Fighter II in February of 1991), at the time still immensely profitable and still incubating the most cutting edge hardware. But Yoshida’s credits, including two as a director, show him working in the home-console market. With the benefit of hindsight, knowing that Technos Japan did not survive as arcades fully wound down, we can probably assume that Yoshida’s projects were considered secondary within the company, a way to augment and extend revenue generated by their arcade flagships.

It’s not hard to imagine a world where, by 1990, the company had begun to fully reverse that relationship, with Yoshida as their premiere director. That’s not what happened. But the industry as a whole eventually caught up with Mitsuhiro Yoshida, which is what I want to talk about today as we honor his legacy. I don't know a lot about his post-Technos career-arc, or how he ended up as a ‘Special Thanks’ name in the River City revival still underway in 2022. I also do not know much about Miracle Kidz, the company that announced his death.

But I know a lot about River City Ransom (in the UK, “Street Gangs”), a lot about its forward-thinking design, a lot about its influence on 'brawlers' or ‘beat-em-ups’ as a genre, and a lot about its place at the peak of the NES library.

Ahead of its time, inventive, ambitious, cheeky, mischievous, flexible, knowingly absurd - that’s River City Ransom. Also an indispensable title in the history of co-operative play (ahem, as we used to say in the olden times, "2-player"). A big success in America in 1990, during the console's final year as Nintendo's flagship. A game that continued to be played and talked about throughout the 90s precisely because of the way it was put together, because of the design choices it made to which newer games seemed oblivious.

We don't like to dwell on it, but in the annals of videogame history, you can find moments where a developer puts up a positively heroic effort - they see which way the wind is blowing, they shrewdly adapt, but the ideas don't take hold. Arguably, River City Ransom is a more 'modern' game than, for instance, all three Final Fight games on the SNES and all three Streets of Rage games on the Sega Genesis. But we can only see that with hindsight. In its moment, RCR achieved success, but its experimentations were almost completely ignored. So let's talk about them.

Mitsuhiro Yoshida knew that, however glorious the arcade heyday had been - and his company basically started it, with 1987's Double Dragon - the genre wouldn't survive in an explore-at-your-own-pace, revisit-for-days-and-weeks, at-home model of gaming, unless...

Unless.

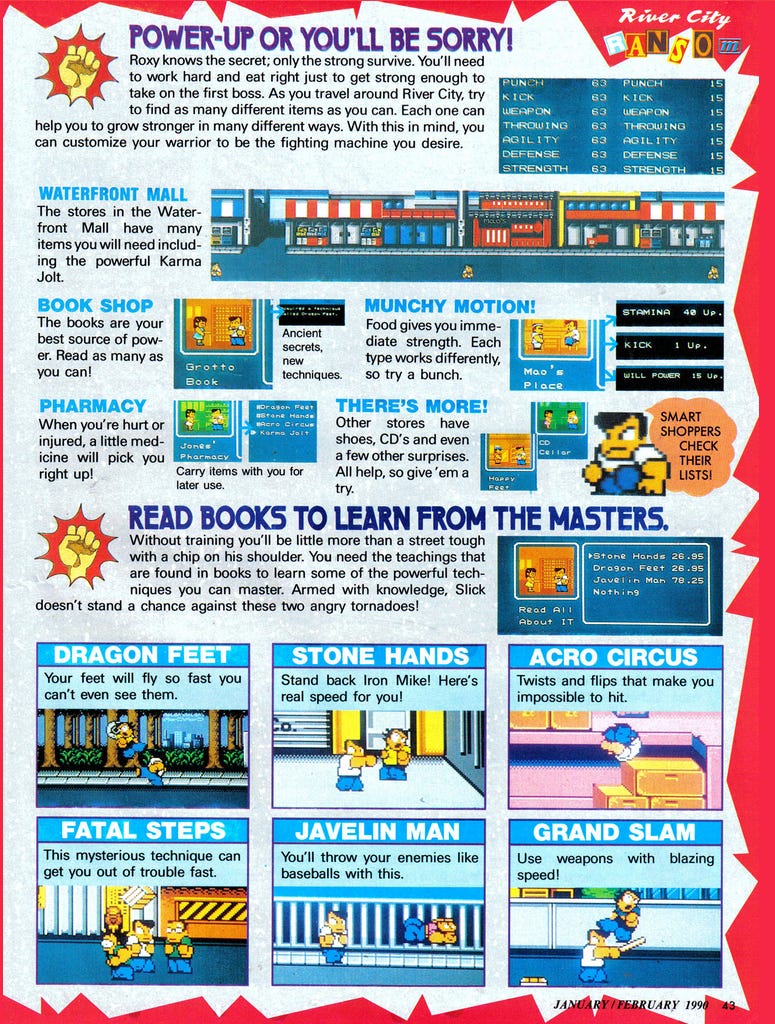

Unless they created a coherent open-world to roam and explore with non-obvious, not-entirely-linear progression, a full decade before "open world" meant anything to anyone. Unless they created a rich layer of strategic progression, with character stats to level up, a wide range of zany combat techniques to learn and unlock, and an array of consumable items to apply as needed. Unless they blended the simple & straightforward brawler template with the more cerebral point-and-click adventure template, where you piece together clues about where to go & who to talk to, where bosses themselves may give cryptic hints in defeat. Unless they balanced the game so that anyone could beat it with some persistence but veterans could challenge themselves to beat it with speed and swagger. Unless they infused combat with a layer of uproarious comedy, as you thrashed your classmates with trashcans on the high school basketball court. Unless they shined a spotlight on the idea of moveset, where you have expanded freedom to trounce foes in style and sequence together moves on the fly.

Certainly, River City Ransom has some limitations tied to the two-button NES controller. And by highlighting its many strengths, I do not meant to throw shade on every arcade beat-em-up that followed, some of which I enjoy quite a bit. A full genre retrospective would be an article for another day, but in thinking about the dozens of games in this template made over roughly a 7 year period, it can help to ask three questions.

What is the player's moveset and does it give them a sense of depth and versatility in approaching the game?

Are there longer-term progression mechanics in the game - any sort of stats, gear, skills?

What level of "bullshit" are we dealing with from bosses?

Under this quick-and-dirty rubric, River City Ransom, gets a decent grade for questions 1 and 3 and a high grade for question 2. It's also a proto-open-world game in its structure in a genre where that is (was) almost unheard of.

For quite a few beat-em-ups of the era, the answers to these questions are: 1.) It's limited, 2.) there aren't any, and 3.) A high level of bullshit. The best of RCR’s peers and successors score well on #1, often fail #2 outright, and skate by on #3, barely. If you’re trying to find a game as ‘robust’ or fleshed out as RCR, it may well be a 7-year wait until the arrival of the cult classic Guardian Heroes on the Sega Saturn. But even then, Guardian Heroes remains the exception in its context, released alongside games like Capcom’s Dungeons & Dragons: Shadow over Mystara, a 32-bit Brawler that struggles to carry the genre forward outside of its satisfying graphical presentation (the answers for this game under our rubric would be solid-poor-poor). Shadows over Mystara is fun but also limited and straightforward, behind the curve and leaving many options on the table. It is strenuously ignoring the questions that Yoshida is probing in RCR. And Capcom, rather than ask those questions, departs the field, effectively saying to itself that beat-em-ups were intrinsically insert-credit experiences and that era is over.

Truly wild, that an 8-bit game arrived at much more optimistic conclusions years earlier - broader, deeper, more explorative, more responsive to variations in player approach, more substantial (probably more accessible, too). It’s tempting to think of River City Ransom as a flukey game, a unicorn of its time, one that has no 16-bit or 32-bit heir-apparent.

In reality, it simply took the industry a long time to catch up, so long that the lapse in time unfairly obscures what Yoshida accomplished and how much his successors owe him. It's impossible to imagine the late-00s Xbox Live Arcade resurgence of games like Castle Crashers or Scott Pilgrim without River City Ransom. And, even with some minor quality-of-life ‘jank’ in RCR, it’s debatable whether games from this initial indie-revival wave offer a more polished, entertaining, silly, satisfying, or fair experience.

If you want to know where the spirit of RCR lives on today, in 2022, that's easy. The ever-more popular Yakuza series owes an enormous debt to Yoshida and his team. The sheer scale of any Yakuza game dwarfs River City Ransom, easily by a factor of 10 or 15. Ideas we can trace back to River City Ransom are elaborated on in a frenzied riff. But in terms of structure, spirit, design? In terms of physical comedy and winking shenanigans? It’s a straight line from Kunio to Kiryu.

So, last week, we lost Mitsuhiro Yoshida, gone too soon. But today, the seeds he planted are thriving, and indeed at the root of the most prolific and successful beat-em-up franchise of our modern era.

Well done, and rest easy.